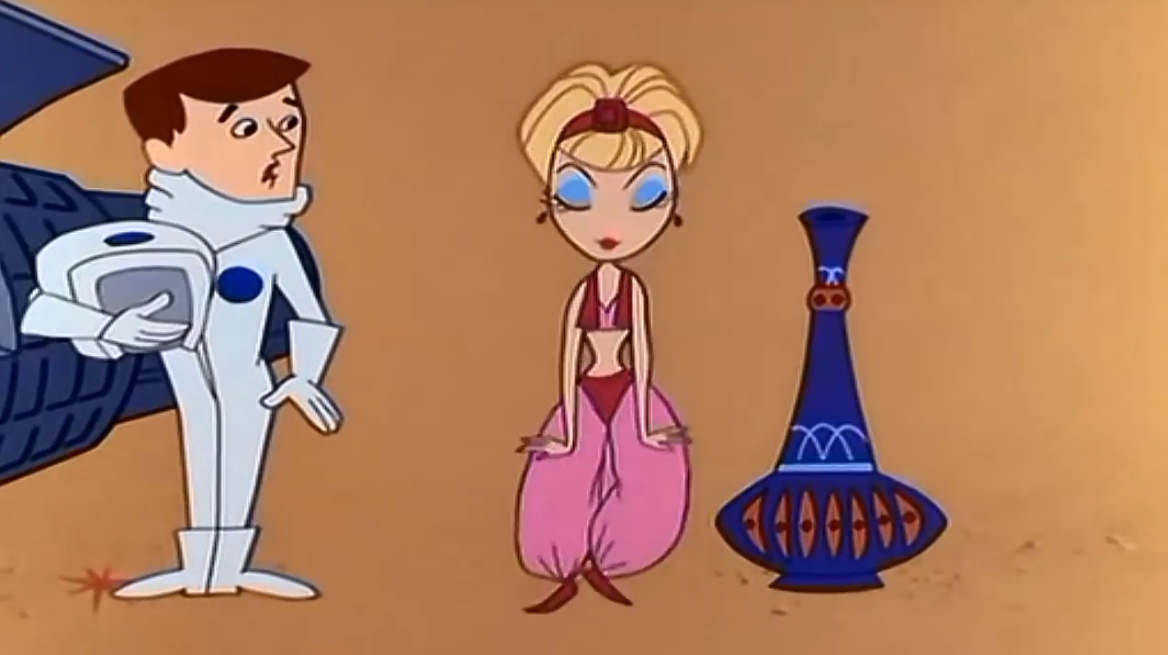

Back in 1964, Bewitched debuted on American television. The success of its Japanese dub would help kick the magical girl genre of anime into overdrive in the late ’60s. If this is all sounding pretty familiar that’s because we talked about it three weeks ago in my post on magical girl anime. But Bewitched and fellow Screen Gems production I Dream of Jeannie would also help inspire another genre of anime and manga, though at a bit of a delay.

In 1978, Rumiko Takahashi manga Urusei Yatsura would debut in Weekly Shonen Sunday. It was adapted into an anime beginning in 1981. In the series, the Oni, a species of aliens, challenge humanity to a game of tag for control of Earth (tag in Japanese is called Onigokko, which means something like “oni’s game”). Earth’s champion is a luckless high school pervert named Ataru Moroboshi chosen by a computer. The Oni champion is the bikini-clad Princess Lum. Lum falls for Ataru, and her attention and affection end up causing chaos for Ataru.

In 1978, Rumiko Takahashi manga Urusei Yatsura would debut in Weekly Shonen Sunday. It was adapted into an anime beginning in 1981. In the series, the Oni, a species of aliens, challenge humanity to a game of tag for control of Earth (tag in Japanese is called Onigokko, which means something like “oni’s game”). Earth’s champion is a luckless high school pervert named Ataru Moroboshi chosen by a computer. The Oni champion is the bikini-clad Princess Lum. Lum falls for Ataru, and her attention and affection end up causing chaos for Ataru.

Magical girlfriend shows are essentially the distaff counterpart of magical girl shows. Where magical girl shows revolve around heroines who use magic to help people and save the day, magical girlfriend shows revolve around a (usually) male protagonist whose life is complicated by the well-intentioned actions of a supernatural love interest.

Magical girlfriends also share a fair bit with harem anime, and the two genres often combine. They’re essentially wish fulfillment, and the protagonist is usually a hapless everyman with a heart of gold.

The girls may be witches, goddesses, aliens, fairies or even zombies. The magical girlfriend with be naive about the real world, innocent when it comes to sex and romance and blissfully unaware of how their actions come across.

In a lot of ways Urusei Yatsura is a parody of the genre that followed in its footsteps. Unlike most magical girlfriends, Lum isn’t Ataru’s ideal mate (in fact, she chases the girl he loves away). And unlike the protagonists of most magical girlfriend shows, Ataru is a pervert and an idiot.

Magical girlfriends embody a Japanese ideal of womanhood called yamato nadeshiko. They are selfless, gentle and demure. Magical girlfriends tend to be helpful innocents who are naive about the world, seeing the best in people and being a bit dependent on their love interests.

Ah! My Goddess from the late ’80s exemplifies the genre with unlucky Keiichi gaining the affections of wish-granting goddess Belldandy. Even the bizarre sci-fi FLCL plays with and parodies the concepts when a guitar-wielding alien chick on a Vespa turns up to harass a middle school boy and fight giant robots. Most magical girlfriend series are shonen or seinen shows, but they can be aimed at girls instead, like Absolute Boyfriend.

Ah! My Goddess from the late ’80s exemplifies the genre with unlucky Keiichi gaining the affections of wish-granting goddess Belldandy. Even the bizarre sci-fi FLCL plays with and parodies the concepts when a guitar-wielding alien chick on a Vespa turns up to harass a middle school boy and fight giant robots. Most magical girlfriend series are shonen or seinen shows, but they can be aimed at girls instead, like Absolute Boyfriend.

There’s not much to say about magical girlfriend shows in general. The concept is concise, and it’s not entirely unfamiliar to Western audiences. Shows, books and movies like Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, Xanadu, Weird Science, Splash, My Life as a Teenage Robot, and Twilight all play with many of the tropes of this genre.

One strength of the genre beyond wish fulfillment is flexibility. As shown by the Western examples above, magical girlfriend concepts can work most anywhere on the spectrum from comedy to drama. They can also play with the tropes of different fantasy, sci-fi and horror subgenres. Sankarea features a zombie girlfriend. Sekirei is a fan service heavy magical girlfriend harem show about mysterious, human-like alien girls who bond with humans and battle for survival.

There’s no clever conclusion for this one. Magical girlfriend shows come in a wide array of tones and genres, but I don’t have much to say about them so I’m wrapping this up. Until tomorrow.

1 Comment