I don’t speak Japanese. I’ve made half-hearted attempts at learning the language multiple times since I was a pre-teen. I still have the battered Japanese-to-English dictionary that I carried in my overlarge coat pocket for most of 8th and 9th grades. Still, a decade later, and I only sort of know a handful of phrases, most of them picked up from anime. But let’s set that aside for a moment.

In college, I spent a couple of years as an English major (and still took upper level lit classes after I switched to journalism). I also minored in Classics, which included two semesters each of Latin and Biblical Greek. I won’t claim to have been the most diligent student, but I certainly found the course work from both worlds engaging and enlightening.

We begin studying translated works pretty early on. Greek epic poems and plays, works like the French The Count of Monte Cristo and the Spanish Don Quixote, Old English Beowulf, and Middle English The Canterbury Tales are all common high school and college freshman fair in the States. But when my 10th grade English class got to Dumas, we read The Count of Monte Cristo not Le Comte de Monte-Cristo.

We begin studying translated works pretty early on. Greek epic poems and plays, works like the French The Count of Monte Cristo and the Spanish Don Quixote, Old English Beowulf, and Middle English The Canterbury Tales are all common high school and college freshman fair in the States. But when my 10th grade English class got to Dumas, we read The Count of Monte Cristo not Le Comte de Monte-Cristo.

While I could, with some effort, read some very simple Greek or Latin, I’ve never read The Iliad and The Odyssey in their original Greek. I’ve never read any of the works listed above in their original language. I have, with the guiding hand of far more expert minds, read a few lines of The Aeneid in Latin, a verse or two from the New Testament in Greek.

But whenever we got our hands on translated works, we were reminded that translation is a delicate process, and a lot of nuances can be lost even between different eras of what we might consider the same language. There’s an Italian phrase for that. Traduttore, traditore. Translator, traitor.

The work of a translator is not a simple one-to-one job of swapping in the vocabulary of one language for the vocabulary of another. Grammar and vocabulary are really only the basics. Context and connotation can pose a huge obstacle. Take this sentence:

That fellow is tremendous.

We can read that sentence in a few different ways. Tremendous can mean both very large and very good. Fellow can mean simply a man or it could refer to a member of some academic society. I’ll admit that the latter reading of fellow would be unusual in a sentence like this, but stick with me. That gives us four different possible readings of this sentence just based on two words having multiple possible meanings.

That guy is huge.

That guy is great.

That member of the Classicists Institute is huge.

That member of the Classicists Institute is great.

We haven’t even begun to address things like wordplay, rhythm, and rhyme scheme. Nor have we touched on literary techniques like foreshadowing. What if the word fellow was used in the sentence to imply but not directly state that the subject of the discussion was a member of the Classicists Institute? The translator must now figure out whether to give this away or to find some way in the language to which it’s being translated to make the same implication.

But we’re over 500 words into this post, and I haven’t talked about anime. Astro Boy or Tetsuwan Atomu was the first anime to be adapted for U.S. audiences back in 1963. NBC aired 104 episodes of the 193 created. Names were changed and episodes were edited to meet the standards of the network and appeal more easily to Americans. One notable change (at least according to Wikipedia) was the removal of a scene where a dog was operated on. This is a trend that occurs everywhere in the arts. Stories are bowdlerized to reflect the beliefs of a new publisher and audience, rather than include something they would find discomforting. (The word bowdlerized comes from Thomas Bowdler, who produced an edited version of Shakespeare that was missing all the really fun, juicy bits.)

In 1967, Speed Racer was adapted from the Japanese Mach GoGoGo. Main character Go Mifune would have his name changed to Speed Racer. The English dialogue, in an effort to match existing mouth movements, is hilariously, frantically fast.

Two decades after Astro Boy premiered on NBC, Robotech went into first-run syndication on American television, meaning it appeared on local stations before it was ever aired on a major network. Robotech was a Frankenstein’s Monster of three different, totally unrelated anime; Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross, and Genesis Climber Mospeada.

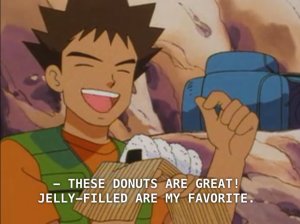

Another decade and we hit the anime boom of the late ’90s. While shows tended to stay mostly intact when they came stateside, dubbing was all over the place. Dubs needed to be easy to make, to be easy for children to understand and needed to fly under the radar of watchful parents. Shows were bowdlerized in some truly ridiculous ways to meet these criteria, and the studios responsible usually weren’t all that concerned. After all, these were kids cartoons, and the kids won’t know better.

But we’re two decades away from the ’90s anime boom, and we’re talking about a much different industry. English voice actors get packed out panel rooms at anime conventions, and popular shows get dubbed so that they can air simultaneously in the U.S. and Japan. Quality is a real concern because the producers know that the market isn’t just a bunch of elementary schoolers hoping to learn new Pokémon tricks from Ash Ketchum.

It’s not that dubs are perfect now, but as this article nicely summarizes, subs aren’t simple one-to-one translations either. I’m not interested in getting into the politics of the linked post, but I do think it highlights the enormous complexity of trying to translate a work across two very different languages and two very different cultures with the added difficulty of a hard deadline.

Now, what have I been trying to say for nearly 1,000 words? I don’t speak Japanese. When I’m watching anime, I’m viewing a work in translation. Even when all parties have the best of intentions, the work that comes out the other side of translation, whether it is subbed or dubbed is inherently, inescapably different from the Japanese original.

Chances are, dear reader, that you don’t speak Japanese either. And in the ongoing and unnecessary argument about subs and dubs, I have to tell you, I don’t think there’s a right choice. I’ll likely never watch Cowboy Bebop, Ghost in the Shell, Dragon Ball Z or Fullmetal Alchemist subbed. Likewise, my first experiences with Non Non Biyori and My Hero Academia were subbed, and it’d be hard for me to watch those shows dubbed no matter which of my favorite voice actors was attached. (Chris Sabat is All Might in the English dub of MHA, and if you don’t think that made me second guess watching the subs, you’re a fool.)

The idea that one of these modes of translation is inherently superior to the other is… well, it’s stupid. I’m not going to sugarcoat it for you. The “dubs are all bad” argument gets most of its steam from shows so old they could have graduated high school and dropped out of college already. Furthermore, the voice actors attached to these dubs are the same voice actors who voice our video games and other American cartoons. They don’t suddenly become bad at their job because they’re reading an anime script.

Some shows are just tonally suited for one take or the other. With a good sub, comedy may work better with the Japanese VA’s original inflections. Meanwhile, due to the generally low key tone of Cowboy Bebop, I fell asleep trying to watch the sub, not because it was bad, but because I lost the rhythm when I couldn’t follow the spoken word.

Anyway, that’s all I’ve got. Subs and dubs both have their place. Don’t be a snob. Watch what feels right. Until tomorrow.

1 Comment